As the damage and economic losses from climate change grow, so too do the emotional impacts of climate change. When an entire island like Puerto Rico is threatened to be uninhabitable or an entire town like Paradise, CA is burned to the ground with a loss of 86 lives, impacts of climate change become much more real to people far beyond the disaster zone.

As the damage and economic losses from climate change grow, so too do the emotional impacts of climate change. When an entire island like Puerto Rico is threatened to be uninhabitable or an entire town like Paradise, CA is burned to the ground with a loss of 86 lives, impacts of climate change become much more real to people far beyond the disaster zone.

It’s important that people not be overwhelmed by that reality, but rather able to both manage their troubled emotions and to work towards restoring a sense of equilibrium in their lives. An understanding of how grief works in the context of climate change can help. I spoke about this recently at Lewis & Clark College and presented “Practical Strategies for Coping with the Emotional Toll of Conservation Work” for the Antioch New England Conservation Psychology program’s webinar series on March 19.

What is Climate Grief?

Grief is an emotion that is a natural response to the loss of a beloved person or thing. Climate-related grief can take many forms, from the manageable twinge of losing a favorite childhood beach to erosion and rising seas to the overwhelm of seeing a beloved family farm succumb to drought and fire—with the loss of livelihood and sense of place that that involves. It will depend on each person’s history and relationship with the land. For example, Ashley Consolo and Neville Ellis have studied ecological grief about climate change among First Nations People in Arctic Canada and also among residents of Australia’s wheat belt.

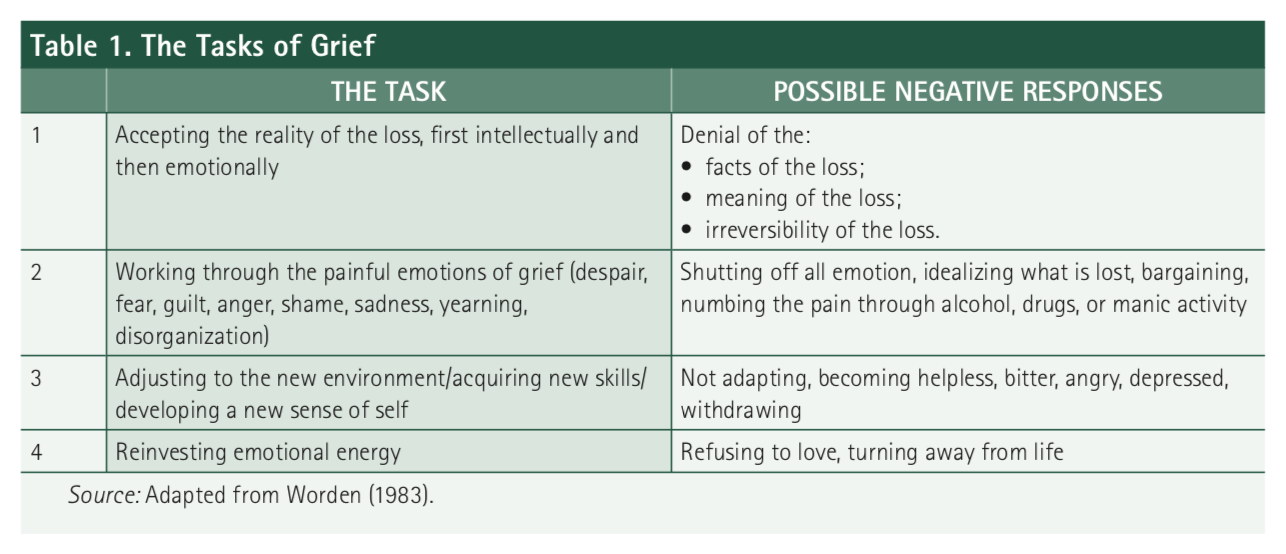

The stages and tasks of grief are well-understood and easy to adapt to the idea of climate grief. These include the basic tasks of accepting the loss and working through the painful emotions like sadness, guilt and even despair. From there, a mentally healthy person must adjust to their new situation and find a way to move towards happiness again. Often, people seesaw back and forth between feeling the loss and working towards their “new normal.”

Applying grief models to climate isn’t a new idea. Rosemary Randall in the UK has developed a very useful model of climate coping groups going back to the 1990’s.

There are many variations on this theme. Grief can be simple or complicated. For example, the loss of an old person who has lived a rich, full life may be simpler to get over than the loss of a young child from an accident. The latter may seem terribly unjust and therefore harder to make sense of or move on from.

Psychologist George Bonanno has shown that people typically exhibit one of the following trajectories in working through grief: (1) resilience where people quickly bounce back; (2) recovery where the bereaved is depressed for a period and then regains their motivation and well-being; (3) dysfunction where the grief is so overwhelming that they remain stuck for a long time; (4) a delayed response in which the bereaved may seem all right initially, but then feels overcome by grief weeks, months or years later.

People Grieve about Climate Change in Character

One of the insights of doing grief work is that people “grieve in character.” They grieve much like they handle other aspects of life. The interesting challenge is that folks with a resilient style of grief have a hard time understanding folks who experience more depression or dysfunction. And vice versa: people who are struggling can mistakenly label those who have a more resilient-style as minimizing or being “in denial.”

I think this applies to climate coping as well. While there is distortion of the facts of climate change by some bad actors in our society, adopting a more resilient or less alarmed response to climate change is not in itself a form of denial.

The Dual Process Model of Grief applied to Climate Change

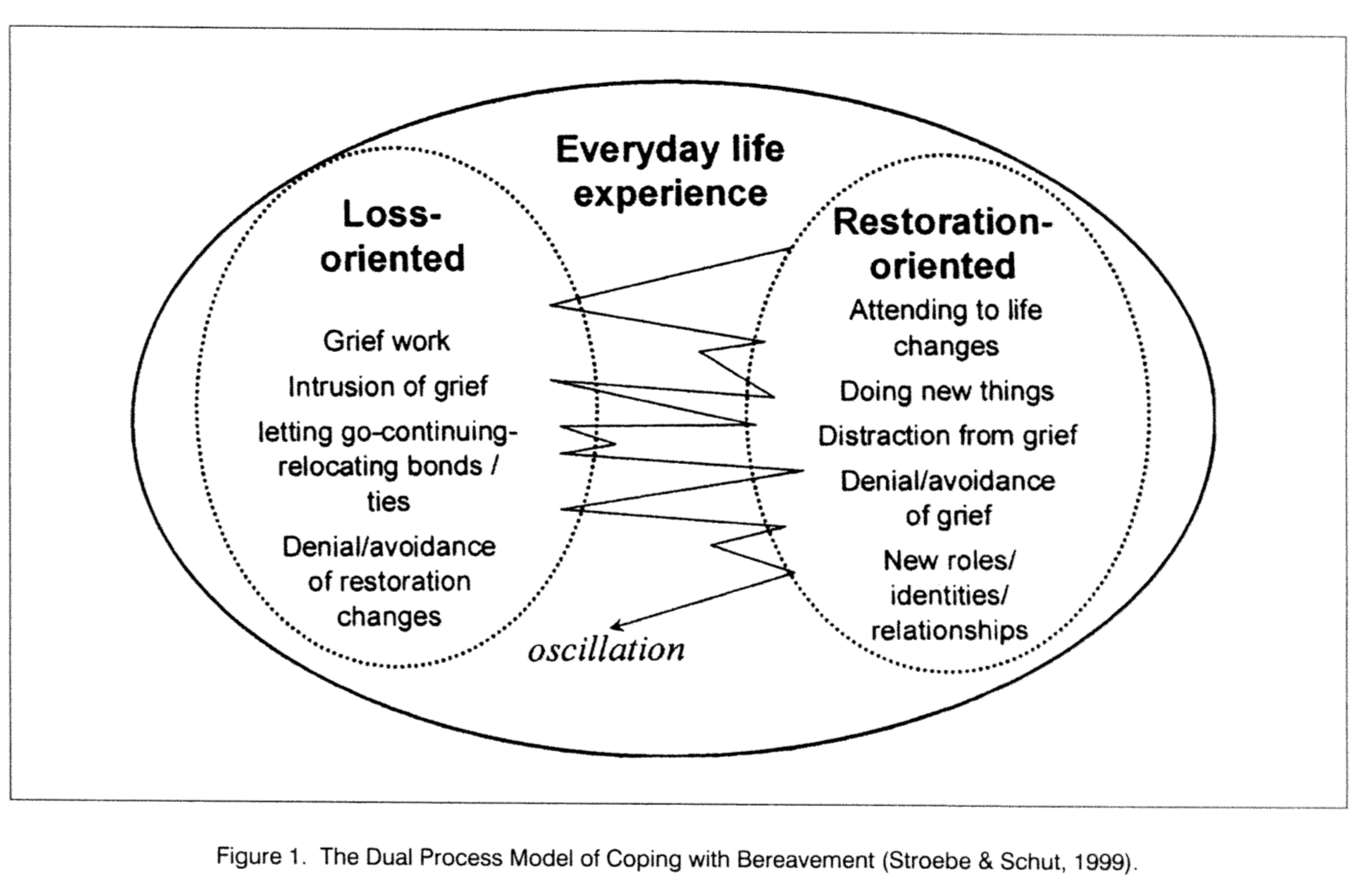

As the emotional impacts of climate change grow and become more evident, people will need to find ways to cope effectively with those impacts. Psychologists Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut from Utrecht University developed a dual process model for coping with bereavement that I find very useful. When applied to climate change, the dual process model suggests that it’s important to balance an acknowledgement of the reality of climate losses while maintaining also positive and restorative approach to dealing with them.

The dual process model has two channels: one that focuses on recognizing and dealing with losses and a second channel that focuses on restoration. As with people facing other losses, such as death of a loved one, it’s normal for people to oscillate between the two channels. Again, the key takeaway is that coping is not a black and white, loss vs. restoration process. Grieving a loss and restoring our lives proceed simultaneously.

The dual process model of grief suggests that people will have a lot of options when it comes to managing their grief about global climate change and its trauma and impacts. Each person will react differently to what is happening. For some, the loss of natural environments and other species, or impacts on people and communities will seem abstract or something they only know intellectually. For others, the loss is deeply personal and painful. For still others, like those in Puerto Rico or Paradise, it’s a loss that completely and permanently upends their lives.

The strength of the dual process model is that it suggests that we must learn to be “at home” with our climate grief while we also work on restoration. There is a middle path that is healthy. If we focus too much on our climate losses, we won’t have the mental wherewithal to work on climate change adaptation and our own restorative activities. Similarly, if we focus exclusively on restoration, pretending as if the losses haven’t happened (to us or others), then emotionally we haven’t dealt with the real losses our world is suffering, and that is likely to take a toll over time.

Coping and Facing the Future

A dual process approach to coping with climate grief offers the potential to help people deal with their normal, negative emotions without being paralyzed into inaction. By seesawing between feeling their loss and moving towards a new equilibrium that makes sense for them, most people should be able to manage their climate grief appropriately.

A dual process approach to coping with climate grief offers the potential to help people deal with their normal, negative emotions without being paralyzed into inaction. By seesawing between feeling their loss and moving towards a new equilibrium that makes sense for them, most people should be able to manage their climate grief appropriately.

It might be a shock that I can speak about such an overwhelming issue as climate change in such matter of fact, or even hopeful terms. But, I have worked with climate for a long time. And I have my ups and downs too. Earlier in my life, when working as a Greenpeace canvasser, I was often paralyzed by the scope of the issues I was learning about.

Adopting a positive approach to coping with climate does not deny the negatives or injustice. It’s important to avoid framing things in black and white terms, a common emotional response when we are stressed. In my personal experience, and with people I known or worked with, building a positive base doesn’t lead to denial or minimization of climate traumas and impacts, it leads to more capacity to take on this complex and troubling information and retain enough bandwidth and creativity to imagine positive actions and solutions.

Sometimes this capacity leads to resiliency, and sometimes to transformation. Climate coping initiatives like Transformational Resilience recognize this.

So, remember—you have many healthy options for dealing with climate grief. A sense of paralysis may occur at times and this is normal. By tapping into the resources of your own character and capabilities, reaching out for support, and recognizing the forces of health and coping that are also present in your life, you can face the future as your best self.

Reach out about Climate Grief. I am happy to speak more.

— Dr. Thomas Doherty

See These Past Blog Posts

- Two Ways to Cope When You Feel Bad about Environmental Issues: https://selfsustain.com/blog/two-ways-cope-feel-bad-environmental-issues/

- Nature-based Stress Reduction: https://selfsustain.com/blog/nature-based-stress-reduction/

- Why You Love the Earth: https://selfsustain.com/blog/why-you-love-the-earth/

References

- George Bonanno (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely adverse events? American Psychologist, 59, 20-28.

- Ashley Cunsolo & Neville Ellis (2018). Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nature Climate Change, 8: 275-281.

- Thomas Doherty (2018). Individual impacts and resilience. In Clayton & Manning (Eds.). Psychology and Climate Change. New York: Elsevier

- Thomas Doherty & Susan Clayton (2011). The Psychological Impacts of Global Climate Change. American Psychologist, 66, 265–276

- Rosemary Randall (2009) Loss and Climate Change: The Cost of Parallel Narratives. Ecopsychology, 3, 118-129.

- Margaret Stroebe & Henk Schut (1999). The Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement: Rationale and Description. Death Studies. 3, 197-224. doi:10.1080/074811899201046.