Nature-based stress reduction is a term I coined a number of years ago. It brings together two separate but very complementary strands of thought about (1) the benefits of mindfulness and (2) the experience of nature and the natural world.

There is a well-established school of thought around the benefits of mindfulness that includes the physiological health benefits of activities such as meditation and yoga and the psychological health benefits that come from calming our minds, improving our focus, and enhancing our mood.

Mindfulness as a therapy tool, more specifically, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), was developed and popularized by Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. I was an intern at the MBSR program when I was in graduate school in the late ‘90s. I was fortunate to get to explore MBSR theory and practice in the relatively early days, and go through the same MBSR program as the medical patients. In the intervening years, mindfulness has become much more established and MBSR is now at the core of many mental health practices.

My vision of nature-based stress reduction was inspired by MBSR and incorporates the health benefits of nature and the natural world. There is a vast body of work in environmental psychology and elsewhere related to this subject. While less well established than mindfulness, it’s becoming common knowledge that connections with nature and greenery, including having plants and natural light indoors, are healthy for us. For example, state-of-the-art office buildings are being designed and constructed with the idea of bringing nature indoors. A case in point is Amazon’s new Sphere Complex in downtown Seattle that features conservatory-like glass domes containing hundreds of plants from all over the world.

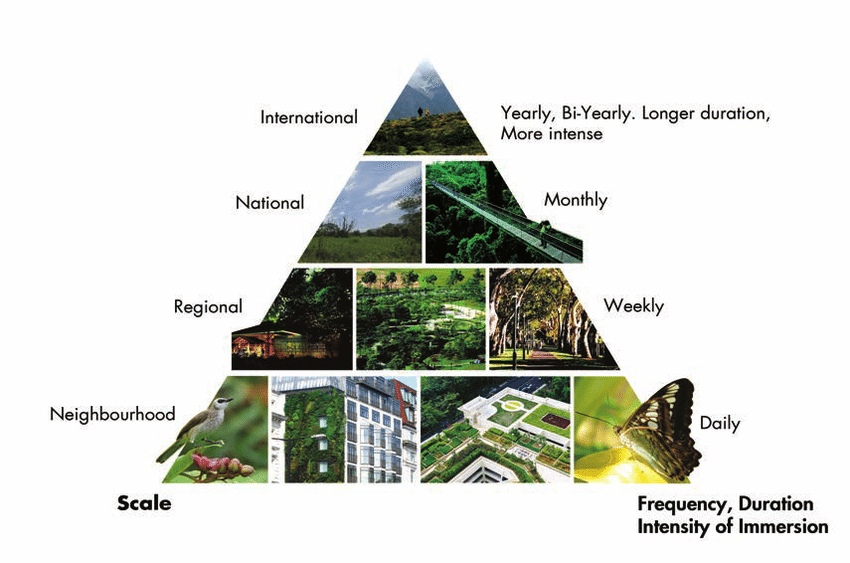

The Nature Pyramid

A good starting point for thinking about ways to bring nature into our lives is the “nature pyramid,” which is modeled after the food pyramid. Urban planner Tim Beatley writes about the nature pyramid as a useful tool for considering how many “helpings” of nature we need to maintain healthy lives.

Our more common experiences form the base of the pyramid. These are our experiences of “nearby nature”—nature right where we are—that may occur often, such as working in our garden or walking around our neighborhood. As we go up the pyramid, we move toward experiences that are further afield and of greater duration. We might go hiking on the weekend, or take a tour or vacation. Our ultimate experiences are at the top of the pyramid. These include going on an extended trip; pursuing a more challenging adventure to really push our boundaries; or traveling to a place that’s particularly meaningful to us.

Some places on the pyramid are “restorative-familiar” like returning to a camp we’ve visited for many summers. Other places inspire “diminutive experiences”—feeling small in the presence of grandeur at the rim of Grand Canyon or looking up at the Milky Way on a clear desert night.

Another way to think about our exposure to nature is along a spectrum. On one end are our ordinary experiences of “nearby nature” in our town or right at home, such as playing with our pets, tending our houseplants, enjoying framed images of nature, or even virtually exploring nature through a video or game. At the other end of the spectrum our experiences are more outdoors, more planned, greener, more impactful, and less technological.

Your Comfort Zone

This leads into consideration of our comfort zone. I spend a lot of time outdoors. I just came back from a camping trip where we were off the grid. The sky was clear and we watched the full moon rise over the free-flowing John Day River in Eastern Oregon. It was strikingly beautiful. We hiked, sat around the fire, and saw animals. It was very quiet and so restorative. For me, it’s something I need to do monthly or quarterly to keep myself feeling healthy.

I’ve camped for years. I have a lot of gear and I can throw together a trip rather easily. For someone else, an overnight camping trip might be a bigger undertaking or even a peak experience. It’s important to think about our comfort level and not underestimate it.

In addition, it’s quite natural and appropriate to be afraid of things in nature. We might jump if we see a snake, and we do have to be careful when we go camping, hiking, or climbing. So, we need to be aware of our comfort zone and be willing to be at the edge of it and push it by experimenting with something new, but not necessarily by throwing ourselves at things so hard that we can’t come back from them. For example, if we go camping, we don’t need to go so deep that we won’t have any access to help should we need it.

Three Factors to Consider

Two important factors to weigh when planning exposure to nature are our personal resources and the level of challenge. When some activity we’re planning seems beyond our resources, we may want to scale back the activity, or if fitness or skills are an issue, for example, we may enhance our resources by training or taking a class. I’ve done a lot of mountain climbing and when those climbs have been demanding, I’ve gone with a group or a leader with experience to boost my resources.

There’s a third factor that also comes into play and that is the meaning of the experience. For an experienced outdoorsperson, a walk in the woods might not be very challenging. But when they walk in the woods and play in the grass with their two-year-old child, that otherwise mundane experience can become quite worthwhile. Even though an activity doesn’t place a demand on our resources or isn’t physically challenging, it may still be meaningful.

Years ago, when I was a professional river-rafting guide, I worked a couple of seasons in the Grand Canyon. One summer, we took a group of differently abled people, who were physically impaired, developmentally disabled, or terminally ill, on a trip through the Grand Canyon. It was one of the most powerful and rewarding experiences I’ve ever had. My routine took on a whole other meaning because of the people I was guiding.

Another aspect of the meaning factor is when an experienced outdoors person takes on a great challenge and pushes so far outside of their comfort zone that they put themselves at risk. Considering the meaning of the experience may help them to think differently about the risks involved, just as it can help us figure out what our goals are.

Another aspect of the meaning factor is when an experienced outdoors person takes on a great challenge and pushes so far outside of their comfort zone that they put themselves at risk. Considering the meaning of the experience may help them to think differently about the risks involved, just as it can help us figure out what our goals are.

A classic dilemma in mountaineering is that the climber sometimes has to decide to stop before attempting the peak because it’s too dangerous. It’s a very difficult decision to make. The climber must weigh the level of the challenge against the meaning and decide whether it’s worth risking their or their teams’ life or safety to achieve the goal. Among elite climbers pushing the boundaries of the sport the risk might be worth it. Most times not. Bringing the meaning into this type of decision-making can be really helpful.

In general, the meaning of the outdoor experience lends itself to the psychology of why we explore the natural world. Searching for meaning requires mindfulness. This dovetails nicely with the restorative effects of being in nature, such as improving our ability to focus, to be creative, and to access memories and thoughts that may be difficult to retrieve otherwise.

As you explore your plans for being in nature, consider these questions: Where are you on the nature pyramid? What’s your comfort zone? What are your resources and the level of challenge? How does meaning play a role? What are your goals?

Contact me to talk more! – Thomas Doherty, Psy.D.

References & Resources

Doherty, T. J. Berman, M. G., Russell, K. C. & Scheinfeld, D. (2014, August). Vitamin E: The Natural Environment as an Active Ingredient in Psychological Treatment. Presented at the American Psychological Association Annual Convention in Washington, DC.

Doherty, T. J. (2015) Video Series on Psychology & Nature

Doherty, T. J. & Chen, A. (2016). Improving Human Functioning: Ecotherapy and Environmental Health Approaches. In R. Gifford (Ed.). Research Methods in Environmental Psychology. John Wiley & Sons.

History of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) at the Center for Mindfulness at UMass Medical School.

Beatley, Tim. (2012) Exploring the Nature Pyramid.

Selhub, E. & Logan, A. C. (2014). Your Brain On Nature. Collins Publishers

Williams, F. (2017). The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative. W. W. Norton & Company