From: The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

“He therefore turned to mankind only with regret. His cathedral was enough for him. It was peopled with marble figures of kings, saints and bishops who at least did not laugh in his face and looked at him with only tranquility and benevolence. The other statues, those of monsters and demons, had no hatred for him – he resembled them too closely for that. It was rather the rest of mankind that they jeered at. The saints were his friends and blessed him; the monsters were his friends and kept watch over him.

― Victor Hugo

From: A Sonnet for Paris

This is beauty, arms open, reaching upwards.

At first the mind refuses it, but the fire

Is ravenous. It will have its sacrifice and does.

While it rages, the gold icon shimmers in kitchens,

On street corners, in bars from there to China.

—Mary O’Malley

As Paris Burns…

Nothing to worry about,

as ancient Church spires

are fueling the fires

that blaze through the night

in the City of Light –

arson’s already ruled out.

—Joe Tessitore

Let us take a moment to reflect on the devastating fire at Notre Dame Cathedral on the evening of Monday April 15, 2019. While undergoing renovation and restoration, the roof of the 850-year-old structure caught fire. It burned for 15 hours, creating a world-wide media spectacle. Damages included the dramatic, flaming collapse of the “fleche,” the 300-foot-tall oak-timbered spire standing over the “transept,” or center, of the cross-shaped gothic cathedral. Less visible was the loss of the intricate oak structure that supported the cathedral’s lead-covered roof.

***

The fire and ensuing media coverage brought back my personal memories of visiting Notre Dame, and revealed the layers of cultural and environmental history that the building represents for me. It was also a personal reminder of how graphic media images can powerfully grab us up out of our day and affect us. I have researched the mental health impacts of environmental issues and the global climate crisis for some time—with insights drawn from media impacts of traumatic global events like the 9/11 terror attacks and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.

Thankfully, there was no loss of life at Notre Dame, but images like that—a world famous building, fire and smoke billowing, a seemingly indestructible icon collapsing before our eyes—triggers surprise and concern, and activates our own fears and anxieties. We are caught between conflicting emotional responses of fascination and abhorrence—the desire to gawk and the desire to turn away. Please know that this is normal.

***

I stay away from news when I am working, having learned to trust that notice of important events will reach me through word of mouth. When I first heard the words “fires at Notre Dame” from a client I met on that Monday, I assumed that this was some unfolding terror attack, perhaps a follow up to the Charlie Hebdo assault. Thankfully, it was not. Still, when I found a moment to scan the online news, I found the videos of the cathedral spire collapsing eerily reminiscent of the images of towers of the World Trade Center falling on 9/11.

When I first heard someone talking about a place crash at the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001, I assumed it must have been an accident. (I had an image of the WWII-era bomber, disoriented by fog, that crashed into the Empire State Building in 1945.) But, it is notable to me now, that the assumption of a purposeful terror or shooter attack is what I—and I think we—have learned. It is a part of our collective psyche. This is one of the daily pressures of our viscerally interconnected 21st century world. News, like ambient urban noise, adds to the background stress loads that our bodies carry.

***

I spoke to a number of clients and friends about the event and was surprised about the range of their reactions. One person felt the incident was not relevant to them as they were not Catholic. Another saw the flames as a “global warning flag.” Another spoke of the irony and entitlement of wealthy business people donating repair funds to the similarly wealthy Catholic Church. Another reflected on the abuses of the church and how this had hardened their hearts toward Catholicism.

As a I reflected on the issue, I began to despair of how to uncover the archaeology of my own reactions. There were so many layers. Even though I have a background as a Roman Catholic, I was surprised that I did not primarily think of the Notre Dame as a Catholic icon. Instead, I remembered learning of the cathedral and its Gothic-style architecture in an art history class. I remembered actor Charles Laughton in the old black and white movie version of the Hunchback of Notre Dame I had seen on TV matinees as a child.

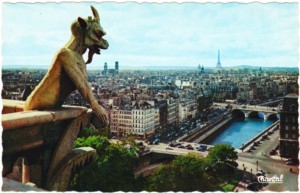

I remembered how Notre Dame and the city of Paris evoked for me a sense of culture and worldliness. I remembered visiting Notre Dame myself while a travelling student in the winter of 1985, in the quiet days between Christmas and New Year’s, and marveling as the grand scope of the cathedral’s interior dwarfed the parishioners at the Mass being said. I remembered later walking around the outside the cathedral on Ile de la Cite while large white snowflakes quietly fell. I remembered getting fresh bread from a nearby bakery and it steaming in the cold air. I remembered the colorized postcard of one of Notre Dame’s iconic gargoyles pinned to my kitchen wall for many years. I remember still later learning of the pagan and Celtic elements in the cathedral and how the vaulting columns echoed the sacred forest groves of ancient druids.

I remembered how Notre Dame and the city of Paris evoked for me a sense of culture and worldliness. I remembered visiting Notre Dame myself while a travelling student in the winter of 1985, in the quiet days between Christmas and New Year’s, and marveling as the grand scope of the cathedral’s interior dwarfed the parishioners at the Mass being said. I remembered later walking around the outside the cathedral on Ile de la Cite while large white snowflakes quietly fell. I remembered getting fresh bread from a nearby bakery and it steaming in the cold air. I remembered the colorized postcard of one of Notre Dame’s iconic gargoyles pinned to my kitchen wall for many years. I remember still later learning of the pagan and Celtic elements in the cathedral and how the vaulting columns echoed the sacred forest groves of ancient druids.

And now, for me, I imagined the modern renovators working amidst the smell of dust and dry wood in the maze of the structure’s ancient rafters. And there is loss in those ancient roof beams. The Gothic style of Notre Dame cathedral called for high vaulted ceilings. To accommodate this, the plans required tall, sturdy oaks from a nearby forest, that were cut down and hauled into place over sixty years during the years 1160 to 1220. It is estimated that workers of the time cleared fifty acres of the ancient French forest, 13,000 trees, each old growth for the time, three hundred to four hundred years old.

***

If you want to get a sense of the memory-feeling I carry about the fire, about all the meanings I have of Notre Dame and my youthful visit, listen to the song “History of Us” by the Indigo Girls.

***

On the day of the fire, French President Macron aptly described many people’s feelings of “tremblement internal”—of feeling emotionally shaken by this event. The bigger point is, don’t underestimate the impact these media images can have. The sense of grief and loss about Notre Dame extends far beyond the people of Paris.

For me, I imagine my youth and I reflect on my loss of innocence. Clichés, perhaps.

From: History of Us

So we must love while these moments are still called today

Take part in the pain of this passion play

Stretching our youth as we must, until we are ashes to dust

Until time makes history of us.

—Amy Elizabeth Ray / Emily Ann Saliers

***

Take a moment to be aware of your reactions to this event. And to other events. An image you see in the media can inadvertently open up the book of your life.

Reflect on how much time you spend watching news like this and remember that it can be healthier to turn it off from time to time.

Be well.

—Dr. Thomas Doherty